Divisions of time and the grid

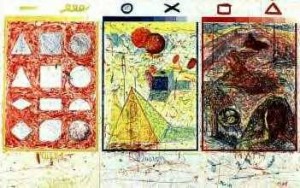

Much like a painter, I think about time as a kind of grid. Below, I’ve posted a work by one of my favorite artists, Pat Steir, whose work sometimes includes her own working grid, thus revealing a part of the artistic process usually hidden from viewers.

There are some musical endeavors that interface with concepts of time or duration in particularly interesting ways. Musical material that comes from the age of Hildegard, for example, invites us to consider the world in a holistic way. Time, the cosmos, the cycles of life, and the progression of a liturgical year, for example, are all interconnected. We may choose to focus on just one of these elements, but we may also choose to take them as a whole (or holy) totality.

This is a long-winded explanation of why I often begin musical compositions by thinking about elapsed time and how the musical material I’ve gathered (whether it’s my own or borrowed from someone else) can guide the way that time unfolds. As a composer, I’m looking for ways to both express something of my own while also letting the material grow and develop in organic ways. If my material can tell me how long it needs to develop, I can create a space, a container for that idea.

So, knowing my own proclivities and knowing Hildegard’s worldview, I start by analyzing her poetry, both in terms of its content and its structure. I notice, for example, that the poem has three sentences, that the first two sentences make up a section, and that the last sentence is set off by itself. (In the hymn, the final sentence is sung by a group rather than an individual, which further marks it as separate.)

O nobilissima viriditas,

quae radicas in sole,

et quae in candida serenitate luces in rota,

quam nulla terrena excellentia comprehendis,

tu circumdata es amplexibus divinorum mysteriorum.

Tu rubes ut aurora,

et ardes ut solis flamma.

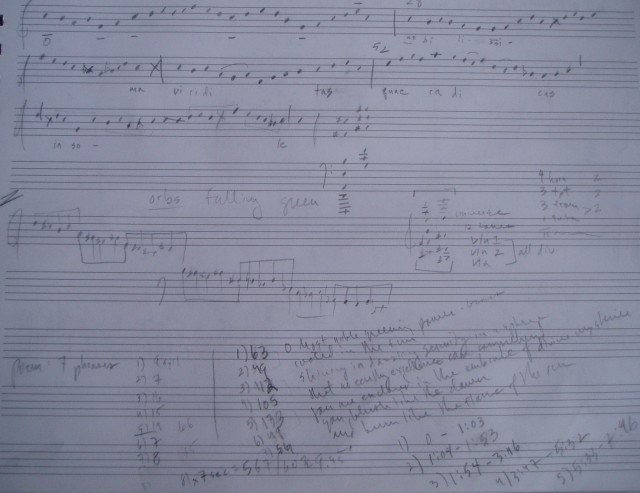

Going a step further, I notice that the poem has seven lines, with a total of 81 syllables in the original Latin. These numbers are important–numerology often lies behind sacred texts, and in the case of chant, we notice that some syllables are stretched to the point where the singer needs multiple breaths to make it through. Below is the first page from my sketchbook, where I’m keeping track of all these observations and ideas. I’ve made my own “modern” transcription of the first line of the chant, as I’m not adept at reading medieval notation.

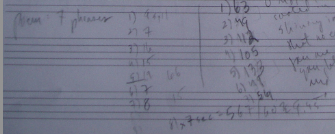

In the lower left-hand corner, you can see the seven lines of text, with their syllable count, and then my decision to multiply each number of syllables by 7 to get a new number. And this grand total, 567 (81 x 7), gives me the duration of the work in seconds (9.45 minutes). These numbers may have been arbitrary to Hildegard (though I doubt it), but to me, they give a clear structure that emanates from the poem itself.

Leave a Reply